As security professionals, we hear about mitigation and remediation on a daily basis. However, these are terms that are commonly confused with each other. In incident response, Mitigation is to minimize the damage of the threat; it is the first thing you do when you realize you have a problem. Remediation happens when the threat is eradicated, and the goal is to get things back to the way they should be.

For example, if there is a compromised device on a network, a mitigation measure could be to block the connection between the compromised asset and their command and control center. A remediation measure would be to identify the malware and clean up the machine. The issue arises when, due to the abundance of threats, we may be overlooking how critical the remediation step really is, and its long-term effect if we skip it. By avoiding the remediation step, security teams are inadvertently allowing thousands of infected devices to make continuous attempts to contact adversarial infrastructure—even if those contacts are interrupted, the attempts will continue. Mitigation alone could make teams believe that the problem is solved when it is only giving them a false sense of security. Let’s explore why mitigation is not enough on its own.

- Mitigation is only the first step: Mitigation should be used as a way to gain time but not as an end itself. Depending on your cyber defense, blocking, isolating, or shutting down may be enough to prevent damage and give your security team time to eliminate the threat.

- Mitigation generates a false sense of security: When you block malware connections or isolate a compromised asset it is normal to feel that your organization is now secure. But what happens if by mistake someone in your team changes the firewall rules, or the malware contacts a new C&C that is not blocked, or if a global situation, like the COVID19 pandemic, forces all your employees to change location overnight?

- Mitigation should be part of a containment strategy: According to NIST “containment strategies vary based on the type of incident. For example, the strategy for containing an email-borne malware infection is quite different from that of a network-based DDoS attack”. That means that you need to design your containment strategy based on each type of attack and take into consideration factors such as potential damage, evidence preservation, service availability, and more.

Which is better: mitigation or eradication in incident response?

Both. You need to mitigate to gain time and eradicate to ensure that the compromise cannot affect the organization. Your goal in the eradication phase is to eliminate all components of the incident (eg: deleting malware or disabling breached accounts) and identify and block the entry points of the compromise to avoid the same compromise in the future if possible.

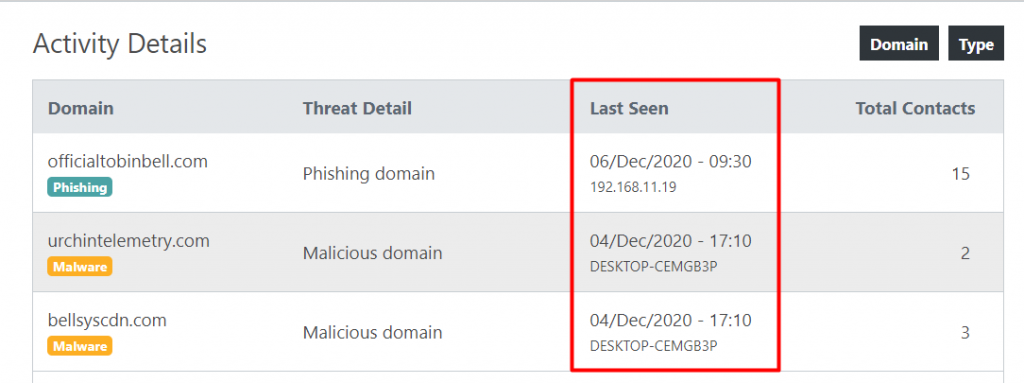

With Lumu it is easy to see if the compromise has been eradicated. You can go to Activity, search for the specific compromise, and see when was the last contact. If you see a contact after it was eradicated there are 2 possibilities. Either it was not effectively eradicated from the affected machines, or it managed to affect new machines.

Another critical step that is often forgotten is the post-incident activity. In this phase, it is crucial to identify the lessons learned during the incident response phase, so as to avoid similar compromises in the future. You can use the NIST Computer Security Incident Handling Guide to understand more about this process.

Conclusion

You should not choose mitigation or eradication. You must do both as they are part of the incident response process. Mitigation is like taking a pain pill, and eradication is curing what is actually causing the pain.